Raffaele Cecco is the king of the Spectrum shooters, no doubt about it. So when he disappeared from the gaming scene a few years ago, we made it our mission to find him and ask about his wonderful games until he was all out of answers...

<< Mr Cecco - as he was at the height of his lame,

and now looking like... well, a fairly normal guy really. Imagine you've just got home from work to find that a sheet of paper has been pushed through your letterbox. On the paper is a telephone number and a request to get in touch with a magazine you've never heard of that's been scribbled down by a neighbour - would you make that call? Luckily for us, curiosity got the better of Raffaele Cecco so he rang us up - if only to find out how the hell we'd managed to track him down... Cecco should be well-known to retro gamers. He sprang onto the scene in the mid-Eighties thanks to the vibrant style of his games such as Exolon, Cybernoid and Stormlord. In the course of his 8-bit career his titles received numérous accolades (including three Crash Smashes and four Amstrad Action Master Game awards) and earned high praise from critics and gamers alike. After working for a while in the 16-bit console and computer market Cecco decided that it was the right time to form his own studio and he launched King Of The Jungle in 1995. Sadly, the new venture was unable to match the glory of Cecco's 8- and 16-bit days and went bankrupt in 2003. Since then Cecco has all but disappeared, which explains why we had to ring his neighbour to ask about getting that note through the legendary developer's door... Retro: What's your earliest videogame experience?

Raffaele Cecco: We'd have to go way back in time to answer this one - more than 26 years I think. My memory is a bit hazy nowadays, but it was probably a Binatone Video Olympics 'games console' that featured various games based around Pong that we received with a TV set that my parents had rented. I was so fascinated by how this thing worked that I proceeded to dismantle it and ended up getting very confused by everything that was inside. Otherwise I remember playing lots of arcade games like Space Invaders, Phoenix and Defender'm the local kebab shops near my school, and finally getting an Atari VCS one Christmas. I was in absolute heaven when it arrived. R: When did you realise that you wanted to create games?

RC: It was when I was about 13 and my parents bought me a Sinclair ZX81. I remember constantly pestering them for it and having to wait ages for the thing to actually arrive. It eventually came, along with a good book about programming in BASIC, and I was absolutely hooked. I wrote a very simple game where you moved left and right and had to avoid lots of asterisks that dropped downwards. Sadly, I could never save my work because the tape loading was so unreliable.

| EXOLON Cecco's fascination with sci-fi emerged again in the superb but tough Exolon (1987), which became his second Crash Smash. This time, the player took control of a soldier who had to negotiate his way through some extremely unforgiving terrain and as with Cybernoid the game featured gorgeous visuals, was pixel-perfect and had sections that could be frustrating beyond belief.

"I was running short of time on Exolon and still had a few levels to create," recalls Cecco. "I vaguely recollect taking one of the-early levels and flipping it left-to-right in order to create a new one. Fortunately, I don't think anybody noticed."

Design short-cuts aside, Exolon proved to be another huge hit for Cecco and it was rather surprising when Hewson never announced a sequel. "To be honest, I don't think the scope for a sequel was as wide as Cybernoids," says Cecco. "Exolon was a much simpler game, and a sequel would have been harder to vary from the original." |

R: Were your parents worried that you joined the industry at such a young age?

RC: I don't think so. I got offered my first job when I was 17 and they were very pleased for me. did mean that I had to leave home, though. I was living in north London at the time and the company, Mikro-Gen, was based in Ashford in Surrey, so it was too much of a slog to travel there every day. Obviously, my parents were sad to see me go, but pleased I was doing something that I loved. R: Tell us more about joining Mikro-Gen.

RC: Well, I'd sent a couple of graphics demos out to both Dalali Software and Mikro-Gen and, luckily, both companies offered me jobs. I eventually decided to go with Mikro-Gen as it had already had a couple of hit games including Automania and Everyone's A Wally. There were also some really excellent people working there that I could (and did) leam a lot from, so it was a very wise move. R: You've worked with Nick 'Captain of Coding' Jones on many games. How did your relationship come about?

RC: Nick started work at Mikro-Gen just before I did and we became good friends. It seemed natural to carry on working together after we left Mikro-Gen, and Nick did several excellent conversions of my Spectrum games for the C64. We kept in touch for a while after Nick left for the USA to work at Shiny with David Perry (also ex-Mikro-Gen), and we met up a few times. Unfortunately, we've now lost touch, but I'm sure we can track each other down again. R: What was it like moving to Hewson?

RC: I initially approached them with a demo for Exolon after I left Mikro-Gen. They were very keen, and they gave me a freelance contract in order to finish it. I never worked from their offices but I certainly enjoyed creating games for them at home even though the financial rewards were never, shall we say, completely fulfilled... They had some good, friendly people there as well including the excellent programmer Dominic Robinson who coded Zynaps. R: You must have felt pretty pleased with the accolades that Cybernoid received

RC: Oh, I was very happy. It was quite surreal walking round WH Smiths and seeing my game all over the front cover of so many magazines. I'd worked really hard on that project and it was great having that hard work finally appreciated by others. R: Was there much pressure from Hewson while you were working on Cybernoid2?

RC: There was always pressure from Hewson! Cybemoid had been such a success that it made perfect sense to do a sequel. Of course, it was similar but for me it certainly wasn't a cash-in. From a purely creative and technical point of view 'rt was an opportunity to expand upon the original technology and concept. R: Exoion was yet another deserved Crash Smash. Did the fame ever go to your head?

RC: Having your work acclaimed

certainly gives you professional self-confidence, but I'd like to think that it didnt go to my head. At the end of the day I was a programmer and a games designer, not a rock star or movie star. I think instances where attempts have been made to portray individuals in the games industry as such have been pretty ridiculous. I remember a phase where any magazine article about developers featured photos of them wearing dark shades, desperately trying to look cool. Very funny! These days any successful game is a big team effort, and I think it's unfair that there are so many unsung heroes working hard behind the scenes.

"AMSTRAD CONVERSIONS OF MY GAMES WERE AN UNWELCOME MILESTONE"

R: Many of your games feature a science-fiction theme - any particular reason?

RC: Not really. When I was younger I'd read the odd Asimov and watched all the camp sci-fi TV programmes like Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers, but I was never a huge fan. From a games design perspective, sci-fi is simply an easy option because there are no limits to what you can do. Fundamentally, arcade games stripped to their bare bones are about geometric shapes and how they interact physically, rf those shapes don't behave in normal, everyday ways they just paint them with some sci-fi elements and ft all makes sense. R: Was this one of the reasons why Stormlord was such a big deéparture from your previous games?

RC: I wanted to move away from the hardcore sci-fi stuff and do something more pretty and fantasylike. I can't say I'm a big fan, but Tolkien, Midsummer Nights Dream and so on definitely influenced me. I'd love to see this kind of theme used in a game for the next gen - imagine how gorgeous and magical it could look. R: Did Stormlords half-naked fairies cause any problems?

RC: Hewson liked the fairies (we all like naked fairies, right?), but I was asked to remove a very subtle but highly suggestive animation on the main title screen. Those fairies were a pain to draw because I couldn't get the legs looking right The breasts were perfect but the lower part of the legs looked absolutely awful, so in the end I just gave up and stuck her in a pot! R: Your games are generally regarded as having gorgeous visuals but being rather tough to play. Was it always your intention to make them such a challenge?

RC: In those days, the term 'learning curve' didnt really exist for me. I did most of the playtesting myself, which meant that over several months I became completely desensitised to how hard they actually were. I assumed because I found the game easy enough, other people would too. I was wrong! I apologise for making people pull their hair out playing my games, and I admire the tenacity of anyone who managed to finish theml R: Have you had a chance to look at the remakes of your classic games over at www.retrospec.sgn.net?

RC: I've looked at the remakes and I'm very flattered that somebody has actually spent the time and effort to reproduce my games, rfs nice seeir them with more up to date graphK and sound. I must say revisiting my games after all these years really does show me how hard I made them. I had problems getting past the first two screens of Cybernoid 2! R: How did you find working on Licence To Kill?

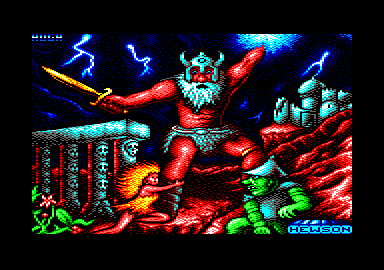

RC: Well, I did Licence To Kill as a freelancer for Domark and it was purely conversion work from the 16-b'rt versions. Sadly, I didn't have any involvement with the film company but I did get an early look at the film at Pinewood Studios, which was pretty exerting at the time. "I ADMIRE THE TENACITY OF ANYONE WHO MANAGED TO FINISH ONE OF MY GAMES" STORMLORD  Stormlord (1989) and its sequel Deliverance were a huge deéparture for Cecco in terms of aesthetics, but still featured the same pixel-perfect timing and solid level design that had made the programmer's name. Stormlord also had a lot more depth than his previous work, and your main character was able to use various objects in order to solve simple puzzles (think Dizzy but with none of the annoying somersaulting}. But while Stormlords production went relatively smoothly it wasn't without problems...

"I remember struggling with a random crash bug and had spent about three days trying to track it down," explains Cecco. "This was really bad news for me, as I normally sorted out bugs within a day. It turned out to be a faulty power supply that would reset the Spectrum whenever it got too hot. Needless to say, I wasn't pleased, and learnt not to blindly trust hardware from that point on." |

R: Solomon's Key was the only arcade conversion you worked on for the 8-bit machines. Was it tough trying to cram the entire arcade game into a humble 8-bit computer?

RC: No, but it was certainly tough trying to cram an entire arcade machine into my living room! I had no source code to work from, just this behemoth of an arcade machine looming over me as I worked. I had to literally play the game from end to end, taking notes and making diagrams as I did so. Needless to say, I became rather good at it - thank God it was on free play. R: So how do you feel about emulation? Do you have a problem with your games being available on sites like World Of Spectrum?

RC: I dont see it as a problem at all, as I don't actually own the rights to my early games; the rights stayed with the publishers at the time - I was very young, nafve and didn't get legal advice. You live and learn.

I could probably apply for some kind of retrospective rights for my original titles, as I was the author, designer and programmer. I don't see the point now though, as they are remembered as my games regardless of the publishers, and I don't think there is much money in emulated Spectrum games. I think emulation in general is fine as long as no-one is actually losing income. Certainly, I think something like MAME is actually an important historical and cultural archive, as it would be a travesty to lose all those old games.

The world of Srormlord was vivid and detailed,

making the game really stand out Mmm, fairies.

R: How did you find the jump from 8- to 16-bit machines?

RC: It was actually very easy. Any new hardware poses initial problems and a steep learning curve, but you had more memory, faster processors and better graphics. Of course, to get the best out of the 16-bits you still had to use lots of tricks. Both 8-and 16-b'rt machines were a pleasure to work with, though, as you were dealing directly with the hardware in assembly language or machine code. There were no high-level languages like C++, libraries or other bumf - just you and the hardware. R: Where did the inspiration for First and Second Samurai come from?

RC: The original idea came from a samurai comic, whose name evades me now, but was about ronin warriors avenging their master's death. There was an artist who was supposed to be designing the levels but he just couldn't get the gist of designing playable maps, so it was left to me at the end, along with the coding. Even though I was designing the levels, this was the first project where I wasn't creating the actual graphics. I'm not an artist and the limitations of my graphics drawing talents had been reached with the 8-bit machines really. R: So which of your games would you like to see updated

for the current generation?

RC: All of them, of course! I'd be especially interested to see if a pixel-perfect game like Cybernoid would work, though, as I'm not sure if you could get that accuracy or awareness of your surroundings in a 3D environment Games like Exolon and Cop-out would simply end up as first-person shooters, as would Stormlord, but with thunderbolts instead of bullets.

To be honest, though, I think many 8- and 16-bit games worked so well in 2D they are best left alone. you couldn't charge £30 for them, but they'd work very nicely as a compilation. R: So which Raff Cecco game

would you say best sums up Raff Cecco?

RC: Of my own titles I'd probably say Cybernoid, as it was the combination of frantic action, colourful graphics, big explosions and sneakily designed levels that became my trademark for a while.

Even Cecco's first game. Equinox, managed to catch the eye of the appreciating Amstrad owner

R: How did you come to set up King Of The Jungle? Was it an easy process?

RC: I'd been working on a freelance basis for a company called Vivid Image for quite a few years and had worked on First and Second Samurai and created the concept for a racing game on the Super Nintendo called Street Racer. Initially, Nick Jones started work on Street Racer but left very early on when he was offered a job opportunity at Shiny in the USA. Naturally he took the job, but courteously 'broke in' new recruits, ex-Domark twins Chris and Tony West. They were car mad (as well as being an excellent programming and art team) so the Street Racer concept was perfect for them. Around the same time Stephane Koenig joined as a producer. The four of us got on really well, especially Steph and myself, and Street Racer was a great success for Vivid Image, getting excellent reviews and selling loads. I'd been getting itchy feet for a while and thought it was the perfect opportunity to break away with the three other guys and start our own company. Basically, we walked into Virgin Interactive with our track history and walked out with a £1 million deal. "INRETROSPECT,THEBIGGEST MISTAKE WE MADE WAS MAKING ORIGINAL GAMES" R: Where did the company's name come from?

RC: The name King Of The Jungle came from an idea I'd had for a beat-em-up based around different animals. The game neversawthe light of day but I thought it would make a great company name. Interestingly enough, we had to get permission from Prince Charles'solicitor to use the word 'king'. They do some checks to make sure you're not a porn company or doing anything dodgy. R: Were you pleased with the games that King Of The Jungle created?

RC: Certainly some were better than the others, but we worked hard and finished all of our titles. I was very pleased with B-Movie (Invasion From Beyond Abroad) as it was different - manically fast with a nice splash of humour thrown in. We finished it on time and it reviewed well. Towards the end, the industry was becoming difficult and the option to do original work was becoming scarcer, so we took on less glamorous projects like Galaga - Destination Earth and Championship Manager Quir, I was just pleased the company was being supported.

Ironically, the game I was most proud of was a playable demo codenamed Explosion Royale that I had put together over a couple of months with our brilliant creative director Joe Myers (now at Kuju). It looked fantastic, with great physics, vehicles and weapons. Unfortunately, King Of The Jungle closed before we could place it with a publisher. R: What can you tell us about King of the Jungle's demise?

RC: Hal How many pages have you got? It was a mixture of inexperienced management, egos and a very difficult time in the industry, as well as publishers letting us down (slow payments and so on). In the end, we had a fantastic demo but no publisher was interested. Many publishers were having a hard time and couldn't take a risk on an original product no matter how good it looked.

In retrospect, the biggest mistake we made was making original games. We should have established a reputation doing licensed products and sequels. Small developers doing original titles have been decimated in the UK, and I admire those that have managed to survive. R: What did you do after King Of The Jungle closed?

RC: After King Of The Jungle closed, Stephane Koenig and myself bought back the rights to Groove Rider from

the liquidator as it was practically finished. We completed it and had it published by Play It, so that kept us occupied for a little while. After that, Steph left for a job in the US, leaving me to ponder on what I wanted to do next At the same time, my daughter was born and, frankly, I needed a break from the games industry after 20 years.

Suitably refreshed, I decided that the games industry wasnt for me any more, as I'd actually stopped playing games. I did a lot of research into web technologies, e-commerce, and the internet in general and concluded that the internet needed a way for the average person to produce amazing web content that goes way beyond what they can currently do with the usual picture albums and blogs. The end result is a project called mypinboard.com, and I invite everyone to check it out at www.mypinboard.com. R: What are your plans for the future?

RC: Well, I still love programming or designing software and my company will continue developing mypinboard.com to become the de facto popular choice for creating amazing web content. The web is still a 'wild frontier', as far as technology and ideas go, similar to the way the games industry felt 20 years ago. Add an instant potential market of nearly a billion users, lower cost development with no middlemen, and you can see why it's so attractive to me. R: So no return to the games industry then?

RC: I had a great time in the past and wo rked with someextremely talented, creative and clever individuals, but as far as the games industry is concerned, I think I'll be resting on my (very old) laurels. Some of the new games hardware like PS3 is stunning and I'll be very interested to see what people create for it You never know, I might start playing games again...

| EQUINOX Equinox (1986) was one of Cecco's earliest titles but it's obvious that it became the perfect springboard for Cybemoid. Many of Cybernoids elements are strikingly similar to those seen in Equinox and it also marked Cecco's first collaboration with Nick Jones.

Taking control of a disposal droid you had to negotiate a series of tricky screens - notice a pattern here? - in search of radioactive canisters. Cecco has fond memories of the game and puts its success down to Chris Hinsley. "All the guys [at Mikro-Gen] learnt a lot from Chris," he says. "He was a brilliant programmer and games designer and really took me under his wing. I learnt a hell of a lot under his supervision." The other aspect of Equinox that Cecco remembers is the sheer amount of work that went into its six-month development. "Games programmers in those days were certainly renaissance men, drawing their own graphics and creating their own sound effects," explains Cecco. "I even remember writing the blurb on the back of the box. Basically the game was a nice and simple arcade/puzzle type of thing, and we simply bolted the story on afterwards." |

|